Thursday, October 16, 2008

Introduction

I called the rendez-vous for Schachticoke because it is one place where, on a day like today, the rocks beside the coldwater falls held a temperature was twenty degrees cooler. A seventy or eighty foot rock face was all that needed to be overcome to enjoy the benefit of the oasis of old trees and plunging water. The topic of the afternoon involved discussing a proposal by a friend who had called earlier in spring. The conversation revolved around a statement of how he “wanted to go somewhere out in the middle of nowhere and hike for a week.”

The call was from one of my eighth grade lawn mowing business partners, Nelson. Nelson had moved from Staten Island, where he grew up with few chains, to our little town in southwest Dutchess County in the Hudson Valley area of New York. On the first day of school in eighth grade, a kid named Anthony Santoro was removed from his assigned seat to isolation in the corner by Mr. Green, who was a pretty mellow art teacher. Whatever Santoro did which prompted the move I don’t know, but I do remember in seventh grade, Anthony provoked a senior to challenge him to stand up so he could take a swing at him. Anthony was perhaps the smallest kid in the entire school and was sitting in the cafeteria, where his head barely cleared the table. “I am standing.” he defiantly shouted. He was not standing. He was messing with the oldest of the Hegarty brothers who was not known for his sense of humor.

Anthony Santoro’s move saw me placed in his spot as I was a late assignment to Mr. Green’s homeroom. I sat down across from Nelson, who I had never spoken with. “Are you taking Spanish?” he asked. He was looking over his schedule intently. At this point, I only knew that Nelson had gotten into a fight last year his first week in his new school, and was reportedly insane. “Spanish?” I said in shock. “You are taking Spanish?”

Languages were not mandatory. As an educational elective, this was not what I was expecting. “Everybody is taking it.” he carefully noted. The manner in which he annunciated everybody meant the hot girls. He was not interested in education or school beyond the social opportunities to hook up and appeared to be testing me.

I signed up for Spanish. During one quiz, of ten or twelve questions, he asked me, “How do you say I don’t know in Spanish?” “Yo no se.” I replied. He wrote yo no se for every answer and immediately handed in his result. He got a D and triumphantly high fived those confident enough to be seated around his storm. At the end of the year, Miss Brenneman, the Spanish teacher, called us aside and politely and earnestly recommended we not take Spanish 2.

By my parents vision, I was supposed to take up with the other eighth grader who founded of Lawn Kings, Collette. He was destined for Dartmouth via Hotchkiss and an immensely successful career. Nelson was all about hedonism and self enjoyment at anyone’s expense. At the same time he was extremely entertaining. He was popular, good looking and most interestingly, he was inclusive to the point where you could make friends with him as long as you were not afraid of him. There was one kid named Bill Ramsey who had a pointed chin and wore the stigma of a back brace to school one year. Rob called him “Triangle Head” and “Ram Rod.” But he was so well known for being insane and an attraction, that Ram Rod couldn’t help but smile. Everytime he saw Bill Ramsey he would shout “Ram Rod!” and high five him. This impressed many kids about Ram Rod and buoyed him socially.

We loved to campout as kids. We had a series of forts we constructed to sleep out in. We played ice hockey in the winter and camped in the woods in the spring, summer and fall. One day, Nelson talked me into taking his father’s new Massey Ferguson lawn tractor up Pergatory Hill to move a fifty-five gallon drum that was welded into a woodstove from the Rob Muenier-Darren McGrath camp to ours. They were a year older and donated the stove to us, as they had designed and built a new one. We wrapped the tractor around an oak tree on the descent and the service mechanic scratched his head telling Rob’s dad that “I had never seen this before” referring to the bent frame. When Rob decided we needed a summer garden for our camp, he suddenly appeared to have been paying attention in class one day. “Slash and Burn, like the Indians!” We, of course, burned down the mountain that day.

Were we were old enough to drive, Nelson sought out whole other order of adventure. One day we went to Candlewood Lake with an eight foot sailboat his father bought for fifty bucks. We sailed out with the wind a couple miles south, oblivious to the other sailboats which were tacking east to west. When it was time to turn around and sail back into the teeth of the wind, we capsized. Rob tried swimming with one arm and pulling the boat. I laughed so hard I almost drown. We did learn to tack that day.

That was only the beginning. Go see Neil Young at the Garden and return to watch the northern lights and do dozens of donuts in the school soccer field? Move to California? His whole life to the present, Nelson is a proven geyser of thought when it comes to having a good time. Twenty years after that day in Mr. Green’s homeroom, we were scaling the granite face at Schaghticoke to review the latest bright idea and whether I was going to accept the invitation that his wife would not.

Rather than blindly agree to jump in the car to the middle of nowhere, and with his bar of adventure now much higher, I wanted to get more information. Sitting beside a twenty foot cascade that fell into a pool, before streaming past large shady conifer and plunging into the Housatonic, was educational. Couldn’t a person plant a large water tank in the yard where the year round temperature is fifty-five degrees, and then pump that water through the house in pipes or, since the waterfall was so soothing and cooling, make a living room waterfall? Wouldn’t that be nice? Then in the dry winter, heat the water and again run the falls for cold weather comfort?

Pulling out official Appalachian Mountain Club maps, I also learned Nelson wanted to fly in on a bush plane and hike and climb Mount Katahdin, the highest point in the state of Maine. Having rarely camped out for even two consecutive nights, hiking and climbing for a week was certainly attractive, especially considering we were talking October in Maine, among moose and trees. However, when you live near sea level and have no mountaineering experience, climbing a mountain that is over five thousand feet high is by most standards, a challenge.

“We fly in on a bush plane…” I cut him off. “We do what?” I asked incredulously.

“We fly in on a bush plane, it costs like fifty dollars.”

“I don’t care what it costs, what are going to land on?”

“A lake.” He replied.

“You’re kidding me.” I said. “No! It’ll be a blast.” he said with a laugh.

Nelson, who gleaned this plan after his friend Frank, having just returned from Katahdin, convinced him of the need to go. I agreed to go provided we run a couple of preparation hikes. Since we live alongside the Appalachian Trail, which terminates in the north on Katahdin, we resolved to make two weekend hikes with packs to train for Katahdin. During runs of eight and then twenty miles that convinced us we had no chance to survive Maine, we gained enough entry level experience to understand our limits. We learned plenty about what worked and what we needed to do in order to at least try. With better equipment and food choices, we decided to cut down the route. Out the window went the plan to land on Lake Katahdin and bushwack to the mountain. Instead we choice to more competent route of picking up the well marked Appalachian Trail forty miles south of Katahdin at Nahmakanta Lake, and then heading north.

Hence, knowing nothing little about much, and much less, Thoreau, on September 30, 1994, I climbed into a loaded Chevrolet Suburban which took me somewhere I should have been all my life, on a walk in the North Maine Woods. Since this running into the wilds of Maine was made for me, I have been back several times and keep tripping over Thoreau’s steps, which are long faded from the trails but resound in his commentaries of “The Maine Woods.” Seems many places I have been by now, Katahdin, Webster Stream, the Alagash, and the west branch and Chesuncook, the man with the feathery pen had been well more than 100 years previous.

Without a single one of his writings in my head, I took an interest in seeing moose, and hiking and climbing rocks, along with a wholly empty head into the place. (One example of the void involved leaving at 5 pm on a Friday evening, with Friday evening traffic though Hartford.) The plan was for Nelson and me to drive all night and jump a bush plane onto the AT in Maine’s 100 Mile Wilderness. Even though sleepless, we would walk eight miles from there before the climbing to the granite top of the monolith of Maine and continuing over the Knife Edge Trail, and down to Roaring Brook Camp ground in bountiful Baxter State Park.

One important fact learned on the trail leading up to decision to take on this challenge was that we knew we were still as green as was likely to be in those woods. This humility helped us to avoid any possibility of underestimation in Maine. Since embarking and returning from this incredible introduction to the northern boreal forest, I eventually read The Maine Woods and learned the details of Thoreau’s wanderings. I also learned that there is a tradition in providing accounts of travels to places such as Katahdin and the west branch etc., which began with Professor from West Point in 1838 and continues today online with bloggers. It seems that visiting the North Maine Woods is such an overwhelming experience, that folks have always been compelled to write up and publish their stories. In my case, having met Thoreau first at the height of Tableland and later at home in print, the want to document the unlikely passage of two Greenhorns traveling in famous footsteps has produced the text of Chasing Thoreau.

Click Here For Slideshow of Nahmakanta to Katahdin

Katahdin:Nahmakanta Lake to Baxter State Park 1994

To some, the Appalachian Trail rambles nearly 2,200 unfailingly blissful miles from Springer Mountain in Georgia, through the eastern hardwood forests, and over the crest of the Appalachian Mountains to Katahdin. To some others, the Appalachian Trail is more wilderness than bliss, and more than most can handle physically and emotionally. Preferring mountain ridge to meadow, and the clouds to the valley floor, she only dips to just above the sea at Bear Mountain, o’er the fjord of the Hudson. It is a trek reserved by default for those who can delight in her secrets and melt into her grace. Looking at the flowers and trees can spare the mind from the grind on the knees. In that idiom, once the soul has been accepted into the spirit of the path, the end to enders find the power to make this epic journey.

For the Greenhorns who decided to hop the trail at Nahmakanta Lake, and then scramble the Northern Terminus to the treeline and beyond, it was necessary to take a test run or two. In this case, doing so could only end up drastically slashing at the level of potential ineptitude that certainly awaited the jump from lackey hiker to aspiring wannabe. Enjoining the spirit of the AT near finish line, came easier than emulating the requisite physical ideal, which only came though a determined regiment of nervous preparation.

On a choking July afternoon so thick with humidity, that perspiration oozed from every port upon slightest exertion, two novices hoped out of the air conditioned SUV and into the high heat of an 8 mile walk. Leaving at the outset of the roasting Sun’s most notorious daily workings was a first mistake. The second was wearing sneakers, and the third was choosing to bring a half gallon of milk in a plastic milk container. Quickly, the agony of picnicking insects attracted to volumes of sweat, produced a steep and miserable first mile up Hammersley Hill on the AT in Pawling New York, and a desperate beginning. Hunching over from the dead packweight, droplets squeezed from the head exploded onto the dry and dust trail before them. Finally on the Hammer into the shade, they stopped to gasp for breath. You could see the bulging blood vessels in the the neck and forehead as they came to terms with reality. This was much harder than any hockey practice.

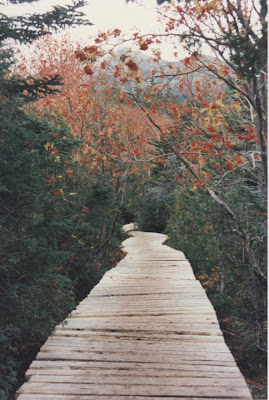

Walking along Hammersley Ridge they entered into swamps and boggs made passable by an impressive network of wooden footbridges. Delightful clusters of mountain laurel strewn about hardwoods of oak and ash grew among a network of forgotten stone walls. At one particularly appealing wall, with a trail opening, became the lunch spot. During the uphill beginning the milk spilled throughout one pack, allowing the pain of chaffing feet in inappropriate footwear to momentarily fade. The test hike was accomplishing its true mission.

Feeble and loud, incompetence is a cumbersome vestment, especially in a crowd. It is a coat all wear in new and different exploits, and for individual durations. One relief found in the trademark solitude that is the Appalachian Trail, is that few are on hand to contemplate the lesser scramblings of her indoctrinates. Thankfully, as here in accessible and easy terrain, the business of education in these elements can be done so in a private exasperation. But not all who would go into the woods are destined to return and the trail ahead in Maine held both prospects, demanding the full attention of the impending traveler.

They ate peanut butter and jelly between compressed strips of what began the trip as Wonderbread, as had a good laugh at the early results. After lunch, they has a smoke on the wall.

“Hey look, ants.” Said Rob. Suddenly they realized they were immersed in ants. On their clothes, in their packs and on their persons. In the ants, they found the impetus to quickly mobilize and resume the workout. After walking through an old growth stand of trees, they came upon the Webatuck Shelter and a hiker bound for West Virginia. The similarity between the stout branches of the old trees and the muscular trunks of this man’s legs was unmistakable. Milky white and devoid of shape, the Greenhorns stood behind their packs to shield their legs from view.

The welcome to the AT - the easy part that is the New York to Connecticut section - certainly was humbling. The seventh mile, up a minuscule five hundred foot incline on Ten Mile Hill in Wingdale, N.Y., was performed so slowly and with such stress and duress, the tendency to laugh in self ridicule became an exhausting distraction. When you aspire to climb a five thousand foot mountain, but can’t handle a small fractional sample, humor indicates some regard for concern. Here on this soft slope, the vision of Katahdin was inspiring the hearty chuckles and reaffirming the urgency with which preparations needed to continue.

The comical practice hike was most austere on the descent, where the only method to walk down the hill to camp sans needles of pain in every detectable leg nerve, required the intrepid hopefuls to walk backwards. This less agonizing but absurd and farcical down climb was discovered accidently and immediately adopted to the Ten Mile River, where they staggered into camp as broken men. As they dropped the backs and headed for the river to cool off, the slime water of the Ten Mile felt like oil and was of little comfort that evening.

Out of the New York and Connecticut woods was borne a galvanized charge to return to the Appalachian Trail. They needed to train their legs and backs and minds to accept the pain and endure the considerable questions surrounding either the futility, or the feasibility, of the Maine pursuit. To put oneself through a challenge is interesting, but to head out and get hurt or lost, putting others in danger is an order of the amateur they wanted to completely avoid. For the protagonist of the pairing, the John Millington Synge quote sums:

“A man who is not afraid of the seas will soon be drownded for he will be going out on a day he shouldn’t. But we do be afraid of the sea and will only be drownded now and again.”

Along with that sentiment, things such as lifejackets and safety awareness preparation also help to reduce the drownded. On this chart, heading off to MA/CT AT was the equivalent to a short seaworthiness test. With a new resolve, a twenty mile, two day walk from Race Mountain in Southern Massachusetts, to Falls Village Connecticut, was routed for early September. With authentic hiking boots replacing the permeable soles of sneakers, a more efficient equipment selection and the benefit of a nominal conditioning regiment, the second test revealed a less foolhardy pair. Even with a finish that saw another strained and painful gate finally finding the car, the charge to convince the expedition’s participants that the destination is attainable; an important item on the Things to do before you Adventure Travel list.

On a crisp, clear and cold Saturday September 10 at 7:00 am, they hoisted full packs at the Race Mountain Trailhead. The sprint up the Race Brook Falls Trail was weighted by a grade that was steep and hard to master. When you plan and map out a hike and buy the food and pack the equipment, shuttle the cars etc. You thrust that pack and head off thinking you are the embodiment of a rugged individual. Then a seventeen hundred feet steeple chase over two plus miles stabs you in the lungs. You sweat and stp to breath and cool down to chills. You are hungry although you just ate before starting. You have to laugh at yourself. In the end since Katahdin is four thousand feet up over five and two tenth miles, the butting heads with Race mountain was a representation of the slope to come, if only forty percent of her length. The twenty mile weekend trek represented half of what was planning to greet them in Maine over the first week of October. Climbing the mountains of northwestern Connecticut, though but a shadow of the White Mountains, is incline enough to conjure an appreciation for tomorrow. To point, the Connecticut-Massachusetts AT Guide book, in characterizing part of the section off Mount Everett, immediately to the north states as follows: “The trail is rough and steep; be cautious, especially when trail is wet.” If qualified experts describe a passage in this manner, the typed words hardly reflect the actual sight that awaits those who climb to this place.

They stopped and ate bananas. Then it was back to the punishment of the pack. They took their time however and with an early start pass Race Brook Camp and the brook plateau before picking up the Appalachian Trail in the Mt. Everett/Race Mountain col.

The ascent up to the summit of Race Mountain was a bit more than a mile, and a four hundred foot incline. It was not an easy mile but they proceeded up the spine of Race in better form than in July. Perhaps it was the cooler weather but the day was still young, and more than six miles remained to the scheduled camp at Ball Brook.

The open summit of Race Mountain appeared in miniature to be what Thoreau describes on Katahdin’s slopes in 1846 where crowds of dwarf trees thrive into the gaps between shelter rocks. From here, a vivid panorama showcasing southeastern Massachusetts, western Connecticut and eastern Columbia County New York, encircled the twenty-four hundred foot crest. The trail south cut to the very edge of the wide ridge overlooking the precipitous drop, which cautions to keep to the Westside of the trail safe from a potentially tragic wind gust. Continuing south almost two miles, lunch was devoured at Bear Rock Falls Camp as the cold water disappeared over Bear Rock upon its business of reaching Long Island Sound. Descending a while into Connecticut at Sage’s Ravine, several other over night campers passed by heading to Bear Rock. Aside from lunch, where a few campers were set up, they had passed no one on the trail today.

They stopped for a break in Sage’s Ravine, where Nelson napped before the thousand foot climb to the summit of Bear Mountain.. Over the next one and four tenth miles, they would be climbing at times, with hands and knees as much as legs. After a short and steep ascent out of the ravine, crossing a hardwood plateau left them an eight hundred foot rock climb over the remaining six tenths of a mile to the summit. That is a grade steeper than Katahdin and certainly good practice for October.

On the summit of Bear Mountain, there is a massive rock monument apparently erected in 1885 upon the assumption this was the highest point in the Constitution State.

Over the summit, which is the highest freestanding point in Connecticut – the highest point being the south slope of Mount Frissell, which peaks in Massachusetts - a fatigued two mile walk to the Ball Brook Campsite brought them to a total of nearly ten miles on the day. From the Race Brook Trailhead that morning, hard but practical miles led to this eloquent camping ground. Situated on pronounced the Berkshire Mountain north-south ridgeline, seventeen hundred feet above the Connecticut shores of Long Island Sound, the grounds possessed a unique charm. The sentry oaks that conceal the camp among dense thickets of friendly Mountain Laurel, have sacrificed height to gain the privilege of looking out over the Housatonic Valley and beyond. Their performance in forming this place has shown why this Appalachian Trail endures and how she lures and embraces her legions. Even the travesty of traditional connotations that are the privy, do not fester here at Ball Brook, where it is as fresh as the fragrances that accent these woods. The open air seat at Ball Brook privy exceeds every expectation, even in the rain. Sitting quietly, this welcomed improvement to the concept challenge of responsible waste management casts all others in mockery, and is a sincerely fresh breath of air.

In the morning, the anticipated turn of the planet flowed as it always had and has ever since. In cycling to face the sun for one more day, the force of the light as it broke through the dawn was such that the whole of Connecticut surely must have awoke all at once. The presence of the sun was so explosive that the eyes begged against a direct look, but instead coaxed a turn to see what the magic hand had just stirred with its gaze.

For these two unwitting walkers, the stir was for the black tea and instant coffee with junkie hunks of sugar. The scrambled eggs and bacon, and fresh soda bread with sweet butter and cream of wheat and walnuts. The swift kick of morning camp tobacco and the glib stride to the open aire john. Along with this sun in these trees, and light fall air, packing out and resuming southbound was a thrilling new day.

Across a wide platform which once staged significant iron ore mines, to a rock outcrop described on the detailed AT map as “Lion’s Head,” then down its rocky spirals to jump off the shrinking ridge as it approaches Salisbury. A sharp left to Route 41 and a quick pace through the adjunct connection of Route 44.

A four hundred foot over one quarter mile invective up the Wetanwanchu and inevitability reminded the Greenhorns of yesterdays ten mile. Lunch with Billy’s view north was functional and scenic, but no more than that. Short enough to make bleak the remaining miles to the car at Falls Village. Upon the fitted chance to melt in that car seat after an eleven mile day and a plus twenty mile weekend, was not anything to be forgotten. From sitting on rocks, walking and sitting on the ground for two days, the car felt like a recliner. The most satisfying discovery that drove home that Sunday however, was that their limitations had sufficiently been reduced to the point where the intention to approach Katahdin from twenty score miles in one week, was much closer to feasibility than simply an optimistic casting.

Establishing individual parameters is but one variable in the equation of the wilderness. Another quantity which defines a production is aptitude. For instance, in deciding on the humble assault of Katahdin, the expedition had initially considered landing on Lake Katahdin and in the absence of the trail, bushwacking a path straight up the mountain. Proving that luck is also a determinant indicator, the plan was discarded. In retrospect, realizing how dumb that plan was, is humbling. Only chance drove them to conclude that the well marked Appalachian Trail and the availability of detailed weatherproof section maps was the competent course to aim for.

As luck would have it, the beauty of October 1, 1994 was extraordinaire in every examination of the word. The runway was known as Spencer Cove led to Ambajejus, or Ambejijis Lake which glistened in the distance. These are bodies whose waters buoyed Thoreau up the wast branch to Pockwockamus Falls, long before the final dam creation made these final expanses to the Pemadumcook, and the Twin Lakes to the south and west. Without knowledge of his meanderings over the same water, the Greenhorns were left to focus on matters such as the urgent fall wind which tripped white caps to topple waves, and a dock and plane that bobbed as the backpacks and the bodies were shoehorned aboard. After an instrument check and presuming the necessary levels of jet fuel and engine oil had been gauged, the loud motor was cranked and the floater began a slow taxi. The sound of water slapping the long grey pontoons, which looked exactly like torpedoes welded to a steel frame and crowned with an airplane, accelerated as takeoff approached.

That it did approach, and quickly, was a large and unmistakable development in the quest as the whimsical intentions of the plane’s paying occupants were irretrievably cast to the wind. Suddenly the engine throttle was gunned - which logrhythmically increased the eardrum pounding volume - and the machine shot violently forward. The pontoons kicked through the choppy surface and everything shook and shuddered. The power required to lift this bird off the runway was reached and in the next moment, a sustained lurch shot the craft skyward, into a new lofty world.

Katahdin Wearing a Cloudy Sombrero

Katahdin Wearing a Cloudy Sombrero With a flight duration of but fifteen fast minutes, the most accurate recollections would have to secure in a watertight color film canister, not that they expected water at anytime, including upon landing, and the focus became to hurriedly document as much as the landscape as possible. Pemadumcook and her tiny islands. Ambajejus, then Passagamet and the Debsconeags to the north. The crooked race of Nahamakanta Stream and finally, on the horizon, the place referred to in the Maine AT Guide as “one of the most beautiful lakes on the entire Appalachian Trail,” Nahmakanta.

The detail and accuracy of the Maine AT Guide is this instance was - on this October morning – was either impossibly understated, or more evidence the Guides maintain uncanny accuracy. The forest that rings round the shores of this storybook brilliant masterpiece was cloaked in foliage that had apparently reserved its peak for this moment. An infinitely blue sky began as eggshell on the horizon and continued straight up to an azure boldness which imbued navy waters and dazzled on the lake bed. These minutes would have to last a lifetime as splashdown loomed at ten o’clock.

Nahmakanta Lake with Sand Beach Cove middle left.

Nahmakanta Lake with Sand Beach Cove middle left.The small cove of Sand Beach held water much nearer to smooth than was afforded at takeoff. The landing was worthy of an ovation but that custom is unnecessary in the woods in Maine. The Katahdin Air official piloting the lift and drop was of the standard ilk that only required him to accept a fair wage for genuine service.

The doors opened the small cockpit space to include the 100 Mile Wilderness, and the last door to pass through in punching this ticket. Getting ashore was an aspect of the adventure not previously anticipated and though a short one, was a challenge. Immediately, a Georgia to Maine thru-hiker appeared on shore with a length of a log to serve as a red carpet.

“Little Drummer Boy” proudly introduced his moniker with a sincerity hinting that if he had packed a red carpet, he would have certainly unfurled it for the moment, but in the absence thereof willed the very same impression with the log. The log was employed by the skeptic but the Viking removed his boots and shoes rather than risk the splash. Not offended, the hosting hiker’s welcome to the Appalachian Trail included:

“This is my 6 month anniversary on The Trail. I started April first on Springer Mountain Georgia.”

With that he was gone, swallowed back into the belly of the beast to finish digesting his journey. For the newly deplaned Greenhorns, the embrace of wonder and amazement was shouting with countless calls, but just a true beginning. For Little Drummer Boy, he was almost too close to the end of his epic two thousand mile walk, a fleeting two percent of which remained. In contrast to the Greenhorns, whose scope and itinerary at full, equated to this humble forty.

Immediately, the lost referred to being lost in amazement. The sight of the bush pilot as he leaves you with your decision to be here, the peaking for the trailhead while photographing everything. This was a giddy moment as the business of settling into a wildscape guessed for months, was done. They were soaking in it as well as soaking it in. This is the time that took forever to arrive and that it came into existence at all was fate. Ultimately when done and forever, kind fate. At outset however, simple fate, with a dose of apprehension. The time when the pack ceases to be a preparatory emblem and morphs into its intended conjecture as a lifeline, and is slung onto fresh backs. A final impatient photograph and the sadness of leaving this brilliant beach never considered, eclipsed by the exhilaration of inaugural and ebullient new steps, directly into the wood.

If getting lost in a wilderness area was not such easy work, surely no one would seek it. Getting lost is so easy however, anyone can do it, not just those who only got off the plane two hours ago. This area is known as the Hundred Mile Wilderness as there are no services between Monson Maine seventy five miles to the south and the general store at Aboljacarmegus Bridge, twenty five mile north.

The plan was to lunch on Nesunabunt Mountain, two miles and change from Sand Beach. Still just a beginning, and climbing, two grizzled Southbounders appeared above, making their way down the south slope. The newly minted hikers had a good hundred yards between each other and the Thru Hikers passed Greenhorn A with a nod. Greenhorn B was curious.

“Where are you guys heading? Georgia?”

The reply was freakish and harrowing even if it was plain wrong.

“No. We’re heading North to Katahdin.”

It was obvious who was who here. Two guys with shiny new equipment and no real grasp on what they were doing and two hikers whose six month stroll qualified them as highly experienced. You can’t hike more than two thousand miles having conquered the likes of the Whites and things like Mahoosuc Notch, and not know what you are doing or which way you are actually going.

“If you want to be heading North on the Appalachian Trail, you need to turn around.”

With that directly ambiguous response, the two trail vets disappeared, heading south.

For the Greenhorns, this was certainly a remarkable development. Two hours into a week in the woods, and this happens. After an extended and throaty display of nervous laughter, they pulled out the maps and began to feel uneasy. Despite the light year variance of knowledge each pair of hikers possessed, there was a zero per cent chance that the aspiring Greenhorns were wrong.

The map was not ambiguous. They were hiking alongside a three plus mile long lake and although they were actually headed Northwest on this stretch, all signs pointed toward Katahdin. Their lack of a compass coincided with a lack of ever using one. Were the Thru Hikers playing some menacing trick? The Appalachian Trail chronicles include instances where its cloak has hid unfortunate cowards and witnessed absolute tragedy. Were these the menacing kind? What a strange and unbelievable development.

They continued up Nesuntabunt. Suddenly, from behind, they heard footsteps…It was the Thru-Hikers…

“You would think that after being on this trail for six months we would know where the heck we were going.” said the one in the lead with a heap of humility.

“My name is Jack The Green and this is Otter.” he informed. “We stopped for lunch up top and took a left off the side trail instead of a right.”

It is one thing to make this mistake on the A.T.. In the Himalayas where the room for error is trace, these could be fatal missteps. For the rooks, they felt more trepidation than confidence even though they were headed in the correct direction. If Thru hikers can get confused, then Greenhorns A and B had to consider this basic tenant of survival a constant threat.

For the Thru Hikers, most of who saw the plane land, 8.3 is a casual stroll, especially in this relatively flat section, the peaceful front lawn of Katahdin. At the same time, the travail for hackers who cut to this trail, this was a straining mosey. The first part heading down Nesuntabunt and the three quarter mile around Crescent Pond was no problem. The descent into Pollywog Gorge began a painful and labored afternoon. From Pollywog Stream to camp, a weak three hundred foot inline over two miles, was wicked on these Greenhorns.

Crescent Pond

Crescent PondEverybody seeking the solitude to be found out here starts the learning curve somewhere and some point. Until you have done so and made something, even the smallest incline seems tough. This felt like the first test hike with sore backs and ground leg joints, sweating and then the Maine cold, posturing a decrepit waltz. Nothing on the AT looked better than the site of Rainbow Stream Lean-to. Fantastically relieved, they were soon sprawled about the shelter in a reclined pulse when joined by another end to ender staring at the Northern Terminus. Packrat, who in arriving sponsored a quick clean up of the hut, was from Connecticut and never hiked prior to deciding to tackle The Trail.

Estimates in any given year seem to point out that some three thousand hopefuls set out annually to conquer Appalachia, inches to inches. Approximately three hundred actually finish the same year. Ice hockey, which helped prepare the Greenhorns as kids for things such as this, is a very intense and physically demanding sport. So is North American football and rugby. The running of the Bulls in Spain is Dangerous. The Ididarod is crazy. But folks, successfully completing the Appalachian Trail is a physical endurance contest of epic proportions.

A two thousand mile course that is flat for only five miles (along the Housatonic River in Connecticut). The rest, with few exceptions including the Hundred Mile Wilderness, is a staircase. You carry everything you need to survive and little else, and you walk for almost half a year. When it rains, and it does rain, the rocky stairs become vernal waterfalls which you must climb up and down all day long until you reach one of the primitive shelters that are spaced 10-20 miles apart. You strain and ache and sweat and freeze with the knowledge that no shower awaits you at the end of the day and you will sleep in accumulating layers of dirt and grime. The next shower maybe a week or a month away. After a few days, you begin to catch whiffs of horrific nasal shards, and you made that with your body. There was no logical room for deodorant in the pack. Even the nominal and basic logistics of purchasing and carrying and resupplying your food stores for six months is exhausting.

You have to carry your garbage until you can dispose of it responsibly. As you pass through cold in spring and unbearable summer heat you must reconfigure your clothing and even sleeping bag, only to freeze on cold July nights at elevation. In Fall you must find the heavy clothes again and sweat during the warm fall days. Mostly young twenty somethings, there are no corporate sponsorships and you are squarely alone against yourself and the elements of out-of-doors. To understate, an Appalachian Trail Thru Hiker is an uncommon athlete experiencing a life changing journey that few other humans could ever appreciate. So the fact that Packrat was a Day One novice transformed by the passage into an embodiment of adventure, was compelling. He had one especially comical story.

As he made his way into the Springer Mountain setting with his new backpack full of optimism, a fellow aspirant point directly at him and howled with laughter at the mass of gear that sat upon his shoulders and back. The comedian dared him to get on the scale provide by the National Park Service at the Trailhead.

Packrat’s burden, at 70 pounds was double the 35 to 45 pound max. brought by most to pull from. This total furthered the delight of the loud man belittling Packrat. Of course Mr. Wonderful, the man who made the fuss, his pack weighed 80 pounds, and it is hoped, altered his conjecture with a thud. Both hikers struggled along for 3 days under the dead weight before finding a store near the trail to ship back the overage. An auspicious beginning that was perhaps 3 days from ending forever.

Another hiker appeared who was continuing his pursuit of the magical miles from earlier years, picking up in Massachusetts. He was a man of few words. In fact when Greenhorn A asked about the campground at Aboljacarmegus Bridge and specifically whether showers were available, Quiet Man replied:

“You been in the woods one day and you’re worried about a shower?”

The Greenhorn did not reply.

The Greenhorns have rarely ever camped without a large night blaze to focus blankly upon. The standard vision of camping in fact, celebrates the fire ring as an institution. So ingrained in the lore is the flame that many people can’t figure out why you would ever want to camp without one. Indeed Thoreau spends as many words to purchase the reader a seat by his evening presentation and all it provided, as his botanical sermons. The advent of the contemporary camping stove and headlamp, with gravitation towards the up with the sun and out with the sun prefect has made a new scene in backwoods trail hiking and camping. For many and for the better, as campfires are not permitted in many places on the AT, including the Maine Woods where permits are required in many areas, the campfire does not burn unattended and does not burn at all. The focus is on getting to the summit and this sees many reach camp, eat and crash.

Taking a cue from Napoleon and his quote that “an army marches on it’s stomach,” the United States Army spend considerable resources to research and develop in theater food rations which only require 2 cups of boiled water and a brisk stir in providing a wholesome meal to troops. This advancement in food technologies has allowed manufacturers to offer product menus which include selections such as shrimp alfredo and beef stroganoff to outdoors enthusiasts. In enabling campers to eat with minimal clean up helps the nomad and the desert, as visitors can now leave an even smaller print. So after a MRE chow down and chunks of chocolate for desert, and the all nighter, The Greenhorns fell dead asleep as the the Thru Hiker cooked dinner and ate some of their remaining rations of noodles. They almost slept through the night but the preaching of Greenhorn A’s pack by a mouse brought him out of a cold sleep straight up to his bag with a flashlite.

Mice are such a large part of the package on the AT that most shelters have mouse proof food bag hangers dangling from the open wall ceiling. These typically involve a small rope with a tin can, with a hole in its middle where the rope passes and is knotted, before dangling a two inch stick for hanging the pack. The mice cannot manure around the tin can to get to the pack. They will get to the pack if the food is not hung. Many campsites also recommend “Bear Bagging” your provisions. That involves hanging your food ten feet off the ground and six to ten feet from any tree or tree branch. By stringing a rope between two trees and then hoisting the pack with a second string over the middle, the food is presumably safe. Tonight, without the appropriate precation and the fact that they were the guests in the mouse house, anything was fair game.

The morning light saw through the timber that the Thru Hikers ate, packed up and split before either Greenie could barley move. They did catch a glimpse of Packrat immediately prior to his departure and wished him happy trails. Much like Thoreaus team, they ate a very similar breakfast along the trail. Greenhorn A would have coffee and oatmeal with bread and sometimes eggs. Green B preferred orange pekoe tea, cream of wheat with walnuts and raisins and bread. Out for a just a week, they were able to enjoy pulling form an Irish soda bread loaf, as well as white and pita for sandwiches. The reluctance to leave the shelter was on account of the joy of petit dejuene and a loathing of slinging up the backpack.

As that was the plan, to hoist the packs and travel on, eventually they got moving with Day Two, a casual six mile stroll to near dusk and a makeshift camp by Rainbow Lake.

Four mile long lakes are not at all close to the Great Lakes in size and not that common a sight in the lower 48, but Maine sure has her share. Rainbow is just another gem casually strew among many diamonds and stars. The trail travels the east side of Rainbow Stream north of the lean-to. Rainbow Stream is interrupted by three ponds known as the Rainbow Deadwaters. At the beginning of the deadwater near Rainbow Lake Dam, stood a fading hunting camp.

The camp faced directly towards the upstart of Doubletop Mountain. The view was framed by tall trees and placid blue water. The camp was nothing more than tables with a few horizontal poles to process game animals and appeared to be an abandoned relic. Here, Greenhorn B demonstrated his accrued wilderness skill level experience by leaving behind a small but vital sack of clothes. He pulled it from his pack in retrieving another item and neglected to account for the green bag until lunch, 1.5 miles further north. This resulted in a three mile trail run as opposed to a relaxing meal. Having crossed the same path three times in the process helped to reveal subtleties that can be overlooked at first glance.

Thoreau’s prowess as a botanist and an arborist rival his prose. The Greenhorns are not educated men, barely smart enough to find this place. Mr. Thoreau’s diligence in documenting the flora and fauna of Maine during the mid 1850s is astonishing. The level of detail provided to humanity saw a man with no camera produce a myriad of images that still are being discovered and will be as long as science prevails in the morrow. Lacking the ability to distinguish a Norwegian Spruce from a White Spruce nor Black from Red, the Greenhorns do have eyes, and the density of the coniferous carpet was not lost even to them. The clear abundance the green needle trees appeared in every size from single stem hatchling to mature giant. They were encouraged to grow anywhere and seemingly on anything, from spongy soil to moss covered rock, to have the effect that these Maine woods are perhaps the greatest spruce tree nursery imaginable. The forest floor that sloped gradually east of Rainbow Lake was carpeted with what seemed like a Christmas Tree mega mall. In some sectors, a single square yard was observed to hold a grouping that appeared to host an annual new sprout, or two, going back decades, and illustrating the developmental processes. Many trees germinated on the occasional moss covered glacial erratic, sending thickening root branches down all sides of the granite rock, resembling a stand of fingers. To walk here was truly a special grant and an education in itself.

Greenhorn B was left with 15 minutes for lunch before a light drizzle inspired the walk to start up again. The peanut butter and jelly was not staid upon the compressed and continually thinning slices of white bread improperly placed within the pack but would have to due until supper.

Arriving an hour before dark at the east end of Rainbow Lake, they set up camp and looked forward to that highlight of the evening camp that is dinnertime. In the deep woods after a day on the move, that hour becomes a very happy time. Every aspect of the meal from preparation to consummation is delightfully gratifying. Just the knowledge that the day’s work is done and the pack you slogged for miles is getting lighter by one meal, helps the mind unwind.

Maybe you have to walk here, carrying the load to understand. The absence of distractions associated with civilization often produces a tunnel vision focus on the primordial need to eat. It is an important psychological aspect of such venturing, but only one of many delicious slices of this wild spread. At this moment, many of the unknowns and questions of what would it actually feel like to in be here were replaced with the new memories and a more in tune anticipation for tomorrow. It was a good feel and it was empowering, and liberating. It felt more like living was a true gift as opposed to just something you do on account of birth. The job and the bills and the depressing pressures of life as many people know it seemed not to matter or exist here as ultimately, this place did not recognize our incessant world. The concerns were curtailed to the present and were of the personal wellbeing and safety variety. Food, shelter and the weather.

Tonight the weather was holding, and rightfully cold in a Maine October. But they were still vulnerable to the elements and their own limitations, which were always at the top of the stack of concerns. It was here, during dinner they discovered the tent they bought for $39.95 was a kid’s tent. With a determined wind blasting off the lake, the irony of a dinner consumed in a 60” x 60” concubine, amongst a vast wilderness, was not lost on either eater.

Whenever the obvious flares, and you are tired, it is easy to laugh. Better laughter than panic. When you know going in that you will be in the least, compared to the status quo, being humble is as much of a survival skill as anything else. You are more apt to learn something. The little tent footnote was discounted by the pure joy of eating and crashing to sleep on the soft sponge that comprises this gorgeous forest’s floor. No need for a fur twig bed on this ground.

After a morning hike to a small pond, they saw a mink, before returning for a regular comfortable breakfast. Soon but not too soon, they broke camp and resumed north.

Day Three was a bit overcast as they ambled up the Rainbow Ledges. At six miles per day, even the Greenhorns eventually rise to the challenge. The stroll that eventually led them to the camp at Hurd Brook, was relaxed, and a time for some picture taking. The subject at the height of the land summit of Rainbow Mountain was devastated by fire in 1923 and it has been slow to recover. The soil of the open space is extremely delicate has eroded nearly to the rock, and the trail through here looks like a concrete sidewalk. Without a photo to compare the Rainbow Summit to, the guess is that this chunk of the Rainbow hectare may be a bald cap very soon, before the forest decides on whether to restore the tract. At present the clearing sports a reported knockout view of Big K soaring overhead. A bleak analogy would be that of driving on the Foothill Freeway in Glendale and missing the San Gabriels in the smog, where after a good winter rain, you can see the snows on the peaks in The Angeles from Anaheim. Here, the overcast wiped out the big moment but was viewed as a disappointment. Seems the cloud that hid her from Thoreau in September of 1946 was back to cling to the jagged edge of the monolith for another party.

Open Summit of Rainbow Mountain

Open Summit of Rainbow MountainDescending from the Rainbow Ledges into the small crook at Hurd Brook, they met more Thru Hikers. Coogliact was one and later, Little John appeared and answered the question of “Where do you live?” with “Right here right now.” Enough said.

Next to climb down from the Ledges was a husband and wife team from California who had previously hiked the left coast version of the A.T., known as the Pacific Crest Trail that runs from Southern California to Washington State. The Tortoise and The Hare enjoyed the Pacific Trail so much they came east, and seemed to be about to conclude another magical carpet ride. After 2,100 miles, they were actually singing as they made their way to camp. They triumphantly noted they had encountered a majestic bull moose at the East End of Rainbow Lake, right where the Greenhorns had camped.

By now the Greenhorns had figured out that Thru Hikers of the Appalachian Trail adopt nicknames or monikers for the walk and use these names to sign in at trailheads and in shelter journals, partly to account for there whereabouts and presence on the Trail. Coogliact had been the fourth hiker of the five they met who said “Oh you are the guys from the plane.” The 5th hiker was Little Drummer Boy who had happened to meet them at the plane.

Little John and Tortoise and The Hare also figured this out in moments. Yes, The Greenhorns were the guys from the plane, adorned with large 35 mm cameras and shiny new clothing and equipment. They still smelled closer to a deodorant stick than any Thru Hiker had in weeks. So Greenhorn A and B, feeling out of place, accepted encouragement from Coogliact to christen themselves with trail names. Greenhorn B chose Paleface, a self deprecating admonishment of his whiter shade of pale Irish skin tone. Greenhorn A selected Hollywood, which was also a slight of self crack at his un-Thru Hiker-esque, touristy appearance.

With the baseball bat platform shelter that is a level of three or four inch round poles, as opposed to planks to lie on, taken by the quartet of Thru Hikers, Greenhorns Paleface and Hollywood pitched camp, conceding the lean-to, as is A.T. custom. They wished the players happy trails and crossed the brook over to a natural platform area. Under the Katahdin cloud, which dampened the sky to produce occasional sprinkles, but did not disaffect the adventure, they pitched the small tent and strung a tarp over head. They were in the stand of a seemingly interconnected grove of cedar, or arbor-vitae as they are known. It was a kind of spooky plot where it felt like there were eyes in the forest, or that the trees themselves were watching you. These old trees have seen so much and cooly held that advantage aloft to confront the wide eyed walker. They must know the secrets of the moose as he swaggers by, and the bears who sleep in their midst, but they do not give them up. Rather they stare in appearances, and cast irregular shadows that turn to monsters in the imagination of children. A very aromatic, but eery place.

Just before sunrise, Paleface awoke and followed what could only be a moose trail, down to Hurd Pond. Camera in hand, he waded through a half mile strand of young 8 foot trees growing in troop formation on a lost dirt road. Without the ability to see ahead more than a few feet, the thought occurred that there was at least a chance of literally running into a moose. A pumping heart raced closer to the water hole as the procession of dawn lighted the sky. Down at the peaceable pond, there were only the simple delights of tranquility and Nature’s pallet to behold. No moose. Still, he waited for one to come out as it looked like would happen anywhere along these shores. With the morning songs of the toads and birds unable to call the moose, Paleface headed back to camp for tea and breakfast with the cedars.

Day Four was as lazy and carefree as is possible for anyone fortunate enough to breathe the air in Maine’s Hundred Mile Wilderness. With but a few miles to reach the General Store at Abol Bridge, this pace of hiking was unusually well suited to Paleface and Hollywood. Unhurried and recreational, this was exactly the type of introduction to the out-of-doors a proper curriculum should include. The first day was a good wake up call and each day since has been easier to walk through.

Coming out of the 100 Mile, they saw a sign that only those who had flown in could possibly miss:

“It is 100 miles south to the town of Monson. There are no places to obtain help or supplies until you reach there. Hikers should not attempt this section unless they are carrying a minimum of ten days supplies and are fully equipped. This is the largest wilderness section of the entire Appalachian Trail and its difficulty should not be underestimated.”

If you did not see this sign before you entered, such as happened with this team, it sure is comforting to read those words upon egesting unscathed. The sign is there in plain English and obvious, and is evidence that people have gone in there unprepared, to suffer unknown fates. The topography of the 100 Mile section varies greatly between the first half and the last half. From Monson heading north, the first fifty miles are much more difficult than the back fifty. Unwittingly, and as luck was with them in these plans, they picked twenty five of the most remote miles in the northern boreal forest. These also happened to be the flattest and easiest twenty five on the entire AT.

Down at Aboljacarmegus Bridge, they saw their first moose. Three in fact. They all drove by in the beds of pickup trucks. It was hunting season after all, and moose don’t always hide. The Abol Bridge General Store, being miles removed from the nation’s electrical grid, operates with a loud generator. Although they were well stocked, lingering at the store was agreeable on a couple different levels. One was that the store was heated. When the temperature is in the high 50s to very low 60s, it takes no time to become chilly. The rediscovery of external heat sourcing was like any other wilderness survival component. The resplendent warmth took on a miraculous valuation. Out here, it is bit unnerving to reflect on the manner in which people take for granted basics such as warmth, food and shelter. The store was also an interesting diversion in that all things considered, shopping out here was odd. They bought cigarettes, which were an ironic sight on The Trail.

Just as vigorously as they wholly engage in a supreme athletic mega marathon, many Thru Hikers will drop the packs whenever a little Trail Magic appears, and party. Trail Magic is the phenomenon of benevolence in which trail sympathizers, mainly veterans of the corridor, show up at a trail access with provisions. They heard stories of such instances where people have flown in burgers and would cook them up for passers by.

Along the trail, they met a fellow named Wandering Jew, who was not wandering at that moment. He was focused on writing a note in the soft mud with a stick to a Thru Hiker yet to cross over the west branch of the Penobscot at Aboljacarmegus Bridge. The final parade on these last days of the enlightening amble was getting emotional.

They passed Sundown and Lorax who had stopped to tend to some concern. Before doing so, Paleface snapped a picture of the pair as they hiked ahead on the path. Both Hollywood and Paleface had been carrying their huge cameras on conventional neck straps. Hollywood finally stopped and hooked his picture machine to his backpack out of frustration from the incessant sway of the Canon EOS. He was also frustrated because there had been no live moose and less bear. The cherub omnivores are common in Southern New York State, moose are not. The purpose of choosing the home of the moose as a destination was based at least in part, on the prospect of seeing his majesty in his element.

As it turns out, all it took was for this camera to be put away to coax Bullwinkle to appear. In this case Grandma Bullwinkle. The old cow only ran 20 feet at a time as they tried to get that trophy shot. Paleface had his camera readily available, later joined by an incensed Hollywood, who had to drop pack and reconnoiter before shooting. Even if it was a feeble old cow, the blood was back into the veins on the lazy afternoon. The adrenalin thrust the adventure back to a pulsating rush. Suddenly every black log in the lateral underbrush and trees appeared to be a sleeping moose.

The excitement was annulled to a smidgeon at Katahdin Stream. With no bridge able to survive the torrents of spring melt water, the not too deep stream was a hop skip and a jump to cross, if you did not have a thirty five pound counterweight on your back. They paused at the stream where some many had dwelled. The habit of setting down in this spot so close to the end was not hard to pick up, unlike some of the river stones.

The fact that some were picked up was evidenced by a happy group of three stone balance rock towers. It only took one river stone media artist to inspire the collection. A good sized rock balanced on an embedded boulder and topped by a small capstone. There was no debate about whether they should contribute to the exhibition; they simply got to work looking for stones.

During the session, Sundown and Lorax passed by again. Told of the moose they were mildly impressed. They had seen a share of the large deer family members being this was there 260th mile in Maine or close to it.

For experienced hikers who have become one with the pack, Katahdin Stream was no problem. For Paleface and Hollywood, it was a nervous, but not an unsuccessful crossing and occurred after completion of their contributed works in stone.

River Stone Gallery, Katahdin Stream

River Stone Gallery, Katahdin StreamAn hour before dusk, they rejoined the west Branch of the Penobscot. At that point, pitching the tent on the high bank of the big river was an easy decision to reach. By now the small tent was shrinking daily and not smelling any better to boot. The door was kept open facing the river to extend the leg room and exhaust the interior.

In the morning, they were approached by a father/son hunting team. No less friendly than any of Maine’s finest, the local woodsmen were happy to talk.

With a “Pepperage Farm” accent as thick as a lobster sandwich, the son – a man of forty-five to firty years – informed:

“Me and Paw is just out huntin’ woodcock and partridge.” With the ock in cock more at ahwk and par in partridge not like tar but pahhtridge, dropping the first r all together.

They told him about the moose.

“Aw that old cow, she been there for years.”

They resumed the hunt, the Greenhorns searched for brighter colors.

This was Day Five. They not only had hiked more than twenty-five miles, met interesting characters, seen incredible sights including a moose, they were now beginning to smell like credible woodsmen. Trail odor varies from simple nausea to inhumane. However, human tolerance levels are known to increase with related exposure to any overpowering stench. Many Thru Hikers will even warn people because the trail odor is so debilitating to the not yet indoctrinated.

They carried these thoughts and others along the west branch before turning to climb beside Nesowadnehunk Stream Falls as they thunder into the mainline below. The Nesowadnehunk, or Sourdnahunk, can be translated to describe a stream between two mountains. In this case Doubletop at 3,488 and rising on the west and Katahdin and her friends to the east. Still not yet in Baxter State Park, they were really only beginning to understand what a special world is concealed within deepest Maine. This staircase which leads to the foot of Katahdin, is a glorious ascent with showered ledges cascading the miraculously clear waters into cheerful pools. Inviting seats and benches of smooth granite offer intimate insights to the gravitational plunge.

The receding glacier that released this fall from the ice, along with the intertwined history of the logging trade on this passage has shaped a geological masterpiece. On account of the violent herds of logs that moved through here a century ago, which were reported to be easily found among the downriver stores due to their bruised and debarked appearances, anchor pins can be found along the sweep. By some miracle, glacially deposited balance rocks survived the logs to stand over the fall. This astounding ledgeway was alone worth the ten hour drive, all the work required to get here, and would be enough to provide for the return trip.

On the Maine AT Section 1 map detail, the landmark description advises “Ford lower branch of Nesowadnehunk Stream. When they say ford they mean walk through the river. When you remember you are in Maine, where a pond is bigger than most lakes and creeks, brooks and streams are what most people know to be rivers, the prospect of plowing a stream with a backpack, is an interesting if not ominous appointment. Back in the drab world of civilization, people cross water on bridges, boats, ferries and planes. In many places isolated places in the world, bridges cannot be built economically to withstand the seasonal crush of water and ice that bores down mountain slopes. As the AT features nearly every type of river crossing experience including this one, there would be a bridge here if it were deemed worth the effort and if it would last. But there was not.

The water was seasonally low but still high enough to knock a person down. Especially a Greenhorn with a precarious pack making an inaugural attempt. It was cold and the appearance of no cinch route left the surge to wait until they could nervously scout a path. The map also advises that “may be difficult in high water.” If the dedicated, qualified and capable members of the Maine ATC who prescribe such recommendations, feel this is a potentially challenging crossing, for this duo, it was almost impossible.

The fording went on to become not unsuccessful and was another example of how solitude kindly shelters fledglings from humiliation. The only thing worse than stumbling is stumbling on a stage. To struggle across with a lackey technique in private, was at least a small relief but not much help. They crossed barefoot rather than soak the boots and persevered despite the legendary numbing cold of Maine water. It was another opportunity to laugh at themselves and the water they escaped. Hopefully that was not something that needed to be repeated.

Crossing into Baxter State Park was muted at this entrance. There are not many way to enter the park and reservations are required unless you are on foot. As hard as it is to get here, it is safe to say this is the gate less traveled through.

After the welcome sign, the exasperating need to repeat the ford brought more laughs as the upper branch of Nesowadnehunk awaited. This “little” branch that spills out of the mighty mother stream and back in, even at second glance, is so big the that it was hard to believe it was considered merely a stream branch. In New York State, there are rivers much smaller than this obscure and voluminous wash. So again it was off with the boots and socks and into the cold water where it was an equally treacherous waltz. After progressing past these two hurdles, the fording took a lot out of them to the point where they walked right past the balancing rock side track. They did stop at the eroding dam at the top of the fall before continuing to Daicey Pond.

Despite the low profile gate entry, no visitor needs a rustic hand carved wooden sign to tell them they are entering into someplace truly unique. The harrowing fords were a big clue, as was the precipitous conclusion of Nesowadnehunk. At Daicey Pond, sitting in the distance between a pair of massive pines, said to be germinated around the time of Thoreau, Katahdin shouts down from her mighty peak and commands all attention. Even cloaked in a cloud, you cannot mistake Katahdin’s presence nor Baxter’s greatness.

If you can alter your bad habits of civilization and conform, you will have an unmatched experience at Baxter. The folks who work at BSP are genuine and very friendly people. They are as peaceful and sincere as people come.

So the Park Ranger was sincerely sorry that the lingering cloud spotted on Katahdin that entire week was dropping ice and snow the whole time. She regrettably broke the news that the dream of climbing Maine’s proud summit was apparently over. Since in their case, they had planned to continue on over the Knife’s Edge and down the back side to a campsite where their shuttled car was waiting, the Ranger arranged for the car to be brought to Katahdin Stream Camp. Even though they were disappointed to learn of the summit closure, the greater concern was with that of the Thru Hikers who had considerably more vested in summiting than the Greenhorns. How terrible to have come all this way to be turned back.

Or they could wait out the storm? Fatigued, the walking of the two and one half miles from Daicey to Katahdin Stream Camp was, even with tired feet and backs, still captivating. The sweetest autumn air continued to represent, accented by a dense carpet of pine straw. Lively green conifers of every description lined the path. Even a bursting summit bubble, this was a grand concourse. For the Thru Hikers, this little stretch is filled with reflection and even the sad resignation that the their Appalachian Trail adventure is mostly over. Only the terminus remains, if you can get there. Fortunately, the final push to base camp is so beautiful that no one could regret passing here.

Their site was situated just so, that checking on the summit conditions was as easy looking skyward. The occasional snowflakes hitting the camp were also an arbiter. No change on the peak. Katahdin Stream Camp was alive with Thru Hikers. They ran into Coogliact who had incidentally, summited under the cloud. It would appear that as tightly as the general visitor is regulated, and for good reasons, the Thru Hikers are not quite as zealously managed. Given their resume over the summer, these trekkers are much less likely to suffer injury and require rescue. The same weekend the Greenhorns entered the woods, the Katahdin Times reported in the October 4, 1994 edition that the Baxter State Park “Rangers put in a busy weekend.” On the day of the flight to Sand Beach, as they touched down on Nahmakanta, a hiker from Plymouth, Massachusetts was airlifted from the Russell Pond area by the 112th Medivac Helicopter. Later that same day, a Jamaica, Mass. Hiker fractured his ankle near Wassataquik Lake. He was also flown out by the 112th. A party of scientist reported a member missing, who ended up returning. In August several rescue mission were mounted. On Sunday, a fly over of the Mountain reveal three to four inches of snow, resulting in a Class 4 climb, and closure of the trail.

The Katahdin Times also mentions that AT hikers who “choose to ignore the closure and give the Rangers the slip, may be handed a bill for rescue services should they put themselves at rick and injure themselves.” In fact the paper also reports that two illegal hikers actually camped out on Katahdin but with no reason to believe they were distressed no rescue party was sent out and it was presumed they left on Sunday. For those Thru Hikers who make it this far, the risks accompanied them this far and are part of the bargain. With the stated consequences to be what they are in print, the push to summit under closure is a situation that will be ongoing. So despite the closure, they took Coogliact’s report to the shelter where they decided to show at the trailhead in the morning to see what the situation portended.

They arrived at Hunt Trail at 9:20 am. The cutoff to leave for the summit was 9:00 am. Since this was the last five and two tenths miles of the Appalachian Trail, and led passed Katahdin Stream Falls, the trail was open to treeline. The summit was still closed. Prepared to summit, the decision was to see what the trail held for them. Prior to moving forward, a hiker told them to put their cameras inside their coats or the batteries would freeze. Suddenly, they tore up the trail alongside the stream.

If you are familiar with high altitude climbing, the following elevations will amuse you.Katahdin Stream is at 1,280 feet. Katahdin is 5,273 feet. The trail is by all but novice standards a breeze at 5.2 miles. Hiking for the first time without packs, and with some proud semblance from all the preparation to make these steps, Paleface and Hollywood were fast upon the mountain. They crossed Katahdin Stream Bridge at the 1.1 mile marker in no time. They ran by a map noted cave at the 2.70 mile mark without even noticing it, but did manage to have to good sense to stop and turn around with cameras in hand as they approached treeline.

The expanding view behind them of the west branch valley was one of rich textures, spotlighted by the sun through rambling clouds. Looking up towards the mountain, the clouds were still and appearing thick. It was also gusty enough to seem as though the wind was trying to convince the cloud that enough was enough. For shunning the traveler for the week, it was time to blow off this top.

The expanding view behind them of the west branch valley was one of rich textures, spotlighted by the sun through rambling clouds. Looking up towards the mountain, the clouds were still and appearing thick. It was also gusty enough to seem as though the wind was trying to convince the cloud that enough was enough. For shunning the traveler for the week, it was time to blow off this top.

The Knife’s Edge Trail, which they had planned to cross with packs, was the most terrifying ridge either tourist ever had the nerve to lay eyes on. It was such a razor thin crest that the trail certainly passed to the south side just below the ridge. The drop to the Penobscot Valley on this side was so steep that if it were a roof of a house, you would not want to shingle it without a scaffold. But that dangerous slope was the way the trail had to go because the drop over the north and western side might as well have been on Everest. There was nothing to cling to and no way down that cold and dark side other than to free fall about one or two thousand feet. The look was so frightening that it took nerve to muster the courage - or foolishness - necessary to tempt a peer over the edge to Chimney Pond, which at 2,914 feet was 2,366 feet below their own soles.

As they continued to look out from Katahdin, alone with the mountain and their adventure, thousands of eyes surely were looking back at them. Undoubtedly the parting of the clouds was noticed throughout the North Maine Woods, and who would not perchance to wonder what it would be like to be attending on the great podium of the woods? How many had come here before them to find such an otherworld? How many Thru Hikers pressed by schedule and time had summit in the mist of Thoreau’s cloud. Up here, they found many questions. Thoreau, who turned back short of the summit in 1846 and caught nothing more than momentary glimpses off the grand table, reported from inside the cloud. Even here, Paleface and Hollywood were closer to Thing One and Thing Two, than Thoreau. To haphazardly whittle out of a cloud, the thought to climb on this rock, scheme and endeavor for months to enable fruition, and then step into the woods ending here, under these extraordinary matriculations of Mother Earth, is not any easier to believe many years later. The camera reminds that this was no mirage or night dream. This day, October 6, 1994, was like no other before it for the Greenhorns, who would graduate from here and go back to a world where moments as unique and exclusive as these would be much harder to come by. The question being; how Pamola had chosen them for this honor? What were the forces behind the spectacular welcome to this magic table and crown? Has Thoreau joined Pamola to inhabit this kingdom? Does he enjoy to assist in her rewards for the occasional visitor with an experience so overwhelming that it is beyond human description? Did he himself want for these photographs to be taken so that the prize of Katahdin’s majesty may never be in doubt? Did he insist, through this grandiose gesture, that the tradition of the account begun by Professor J. W. Bailey of West Point in 1836 be respected?

It is hard to hold speculation up to be truth and reality has her opinion. She remanded

that the million dollar views were fleeting and just as it is on other far away summits, there is perhaps twenty minutes to celebrate, burn a couple rolls of film and make peace with the fact that this is not a place for human beings to dwell. Having reached the destination at 1:00 pm, a three and a half hour climb, they left this view to its majesty. No others would see this scenery in the sacred state. Not anymore today, or perhaps ever again. The slapping necessity to abandon the light of “the secrets of the gods” to begin the reluctant journey home, was narrow and hard to oblige.

The Hunt Trail on descent was a whole other breed of animal. Where the up climb holds the center of gravity close to the rock as it is crawled upon, the down climb sees the balance shift to a higher perch as a successful landing rock is scouted. Here, as the distraction of the sirens of the forest below seduce a picture now and again, the mischievous wind bullies you to obey the retreat. A compress of stones, some the size of houses, fashions the Hunt Trail ridgeway. On the west shore of Chesuncook Lake, there is a camp known as Sandy Point. Perhaps, in a thousand years, the aggregate of small stones that are pushed by the waves will resemble sands. Currently, they remind of how this ridge may have formed. Chesuncooks powerful waves, slap and grind the stones of Sandy Point into ever shifting formations that resemble the waves themselves. Without a network of video cameras documenting the sculpting of Katahdin’s slopes by the infamous Laurentide Glacier, who can say if the forces that were at play fifteen thousand years ago did not conspire to similarly shape this ridge? Once the shifting waves of permanent ice abated, did ten thousand years of annual ice and snow sit upon the ultimate forms and press them into this shape? Is this great rock actually a casting of several giants with network of tunnels a hundred years long? How much is yet to be learned from her mysteries?

This mountain was still calling to her roses of detail by virtue of the artistry in these most recent placings of stone upon stone, reminding that these distinguished and handsome erratics could also have been laid in tribute to the Native American gods. Certainly both the images and spirits of the moose, the owl and the beaver where seen dancing upon the trail alongside the Greenhorns. Do they reside here to cast aspersions at white men who ignore their contributions to this mountain, or are they above such persnickety and reside here to staff an eternal deploy as Master Guides of the Great Land? Or is it both? After a hard life as a hunter, perhaps the Native soul prefers to retire to the mountain, to be amused by the strugglings of the novice as he clamors along, not knowing where he is going, and even less about where he has been. Should it be one with good potential, these gods may take pity and arrange a safe passage. Much is hidden in these rocks. This was further evidenced when first Paleface, followed by Hollywood, climbed into the mountain and ended up discovering a room at its ceiling, from which they had to free climb down nearly fourteen feet. Was this an interior which conceals other rooms? Is there a network of tunnels that lead to the tomb of the great chiefs? Was this a Native American Pyramid disguised as a solid rock?

Questions are harder to answer on this track. There is no weather station and as I mentioned the train does not climb this high, so far to the north. From a geological perspective, is the mountain that hides so many mysteries in her depths only just beginning to have questions asked about her.

It was a happy, if not bumpy ride. More than once, Paleface urged his friend to slow down. First in 1976 when he got his drivers license and twice more today.

“I’m going twenty-five.” He noted.

He was indeed. On Baxter’s goat path, after days of inching along, it felt like eightty. For the next hour, they pursue the Roaring Brook Camp where they had reservations for the next two nights. The objective was a full day of moose hunting, where at Sandy Stream Pond, this is done with a camera and not a gun as in “A Moose Hunting.” They set up camp with a satisfaction sponsored by the considerable success of the unlikely adventure. They performed nominal hygiene which also contributed to the light atmosphere. Even the accidental spillage of the spaghetti pot onto the picnic table, met more amusement than consternation. Since the pasta was cooked, they just shoveled it onto paper plates – another luxury on the car – and dug in. Tasted like pasta in pine needle tea with a caustic tinge of Baxter Brown paint. After the ten and four tenths hike that totaled eight thousand feet, the pillow worked hard in the night supporting much less fulsom heads.

The next day they eagerly headed for the moose hotspot that is Sandy Stream Pond.

Upon discovery of a cluster of wildlife photographers stationed upon a big rock known as Big Rock, the moose prospectus was spot on. Across the large pond – small by Maine standards – were two moose casually feeding in the water. With the objective of summiting Katahdin in hand, all focus was now on the moose watch. This notion included chilling on the rock and listening to pros, which included Bill Stillwell Jr., as they swapped stories of Baxter Park and other wildlife meccas. Granted bagging Katahdin doesn’t rate as mountaineering, however, concluding an adventure in the company of professional photographers gave the trip an exotic feel. Mr. Stillwell told one especially enjoyable story of a moose who was tormented by a visible cloud of biting flies.

Still waiting for the moose to mosey over from across the pond, more stories followed. He seemed to be good at this and made the morning a great pleasure on many fronts.